On April 3, Governor Murphy signed into law the Elections Transparency Act, just four days after the Legislature approved it. He did so with no fanfare, which was fitting for the shameful piece of legislation it is. As Matt Friedman wrote for Politico, “Nobody wants to own the Elections Transparency Act.” Murphy held no press conference and issued no statement about the bill becoming law, nor did any of its legislative sponsors. But the newspapers weighed in and they were scathing. The New York Times headline that day read “Gov. Murphy Signs Law Decried as Frontal Assault’ on Good Government,” while an op-ed in the next day’s Bergen Record ran under the caption “Phil Murphy just upended a national ‘model’ for regulating campaign finance.”

The timing was a bit ironic. Just one day before the first former president ever to be charged with a crime was to be arraigned in nearby NYC on charges having to do with violations of campaign finance law, the governor of the state next door was taking an axe to its own ability to rein in campaign finance abuses. Contrary to what the name Elections Transparency Act suggests and however good the original intention behind the law might have been, most of it has nothing to do with promoting transparency. Instead, the law is far more likely to boost the power of big money in New Jersey politics, allowing it to drown out the voices and values of voters, thus undermining our democracy.

The new law does this in a variety of ways, including doubling contribution limits, authorizing additional monies for slush funds (so-called “housekeeping accounts” to pay for administrative expenses) on top of that, and eliminating local pay-to-play laws, while loosening the already lax state-wide standard. It also hamstrings the Election Law Enforcement Commission (ELEC), the hitherto highly effective agency whose job it is to enforce the laws governing the funding of political campaigns in New Jersey. Not only does the law destroy the independence of ELEC by giving the Governor (one time only) unchecked authority to fire and replace all of its commissioners without the usual advice and consent of the Senate, but it drastically curtails the amount of time allowed for ELEC to investigate violations of the law. Even worse, it makes the latter change retroactive, seemingly (and conveniently) tossing out three pending complaints against statewide Democratic fundraising committees along with about 80% of ELEC’s entire docket of pending matters.

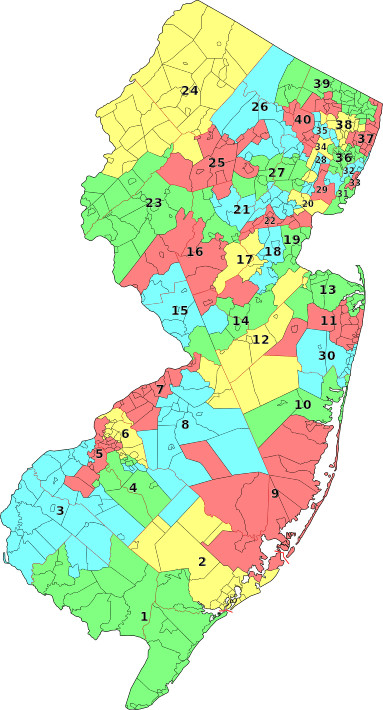

The proponents of the legislation, which passed along almost strictly party lines—only four Dems in both houses voted “no” (Senator Nia Gill and Assembly members Dan Benson, John McKeon and Cleopatra Tucker), only six Republicans approved it (Senators Christopher Connors and Vincent Polistina and Assembly members Dianne Gove, Donald Guardian, Kevin Rooney and Brandon Umba) and an initial Republican sponsor, Senator Steven Oroho, took his name off the bill — tended to justify the legislation based on the disclosure provisions. Those provisions are good as far as they go, but any good they accomplish is far outweighed by more problematic aspects of the legislation.

Following the U.S. Supreme Court’s 2010 decision in Citizens United v. FEC, which reversed longstanding campaign finance restrictions and enabled corporations and other outside groups to spend unlimited amounts on elections, huge amounts of dark money have flowed through those so-called “dark money groups,” which need not disclose their donors, and been used to influence elections. Under the new law, donors above a certain threshold will have to be disclosed and the law’s supporters argue that, combined with the increase in campaign contribution limits, that will shift political giving back to candidates and campaigns, who are required to operate more openly.

Here is a closer look at what the Elections Transparency Act (ETA) does. First, with regard to transparency, it requires independent expenditure committees — nonprofit and political groups not tied to a particular candidate, the source of so-called “dark money” — to report to ELEC campaign contributions in excess of $7,500 and all expenditures regardless of amount. A last-minute amendment expanded the definition of “independent expenditure committee” beyond 501(c)(4) nonprofit social welfare organizations such as NOW, ACLU, NRA, and the Sierra Club, to also encompass 501(c)(6) groups, defined by federal tax law as “Business leagues, chambers of commerce, real-estate boards, boards of trade, or professional football leagues . . . , not organized for profit and no part of the net earnings of which inures to the benefit of any private shareholder or individual.” The bill also establishes a cumulative reporting requirement for independent expenditure committees.

Further, it requires candidates and political committees to report campaign contributions greater than $200, down from $300 under prior law, and all expenditures, regardless of amount. There is also a change from 48 hours to 72 hours in the deadlines for reporting certain contributions and expenditures made within a certain period of time before an election though all must be reported within 24 hours in the week prior to election.

That is pretty much it for the transparency/reporting provisions and it is not even clear that those would survive a constitutional challenge. Very similar language in a law enacted in 2018 was struck down by a federal court the following year in Americans for Prosperity v. Grewal, on the ground that it violated the First Amendment. When ELEC Executive Director Jeffrey Brindle testified before the Senate Judiciary Committee on February 23 in support of some aspects of the bill, he cautioned that the disclosure requirements for independent expenditure groups need to be “narrowly tailored” to electioneering activity to ensure that the ETA would be constitutional, unlike the 2018 measure. That was not done.

Continue reading Murphy’s Law: The Campaign Finance Reform That Wasn’t