Last year’s major federal tax bill –the so-called Tax Cut and Jobs Act— has left many in New Jersey very angry and concerned. And for good reason, even though other aspects of the bill will likely do far more serious and long-term damage, here and elsewhere.

Attention has focused on that part of the legislation with the most obvious detrimental impact on the state and its residents –a newly imposed $10,000 limit on the deduction for state and local taxes.

New Jersey is one of the most highly taxed states, especially in property tax bills. In 2017, the average residential property tax was $8,413 statewide. Four counties—Bergen ($11,566), Essex ($11,696), Morris ($10,219) and Union ($10,863)—had property tax tabs that exceeded the new limit, as did more than 150 of the state’s 500-plus municipalities. In fact, five of them had average property tax bills greater than $20,000, topped by Tavistock’s $31,424.

A report released in March by the Tax Policy Center, a non-partisan think tank in Washington, D.C., concluded that this state would be hit harder than any other in terms of the breadth of the impact from the SALT cap: 10.2% of New Jersey taxpayers would see their tax bills increase, followed by Maryland (9.4%), California (8.6%), Connecticut (8.4%) and New York (8.3%).

And though the bill does provide a small and time limited tax cut for individual taxpayers, the loss of the SALT deduction will offset that to the point that only 61.5 percent of New Jersey taxpayers will get any net tax cut, fifth lowest among the states. And most of that cut goes to the wealthiest.

The fact that the cap hits hardest, and thus appears directed at, blue states such as New Jersey, New York and California, which tend to have higher taxes and to be already shouldering a disproportionate share of the federal tax burden – only adds to the sting.

And thanks to the cap, New Jerseyans will not only pay more in federal taxes but will see the value of their homes decline and have a harder time selling them if and when they decide to do so.

It is no wonder that taxpayers have been seeking ways to circumvent the limit.

Large numbers prepaid their 2018 property taxes in 2017, before the new law took effect, in the hope that they could avail themselves of the deduction before the new law kicked in by lumping the payments for 2018 in with those for 2017. The Internal Revenue Service, however, took the position that that could be done only if the taxing authority had assessed the 2018 taxes in 2017.

The State of New Jersey, like the other impacted states, tried to address the situation through legislation.

On May 4, Governor Phil Murphy signed a law, P.L. 2018 ch.11, meant to allow an end run around the cap by re-characterizing certain tax payments as charitable contributions, which are not subject to the cap. It allows counties, municipalities and school districts to establish charitable funds for specific public purposes. Anyone can donate to them but those who own property within the jurisdiction would get a credit on the next property tax bill. Similar laws have been adopted in New York, Connecticut and other states are working on versions of it.

The IRS responded to such efforts on May 23 with Notice 2018-54, announcing its plan to issue regulations making it clear that the Internal Revenue Code “informed by substance over-form principles,” governs the characterization of deductions.

The following day, New Jersey Attorney General Gurbir Grewal wrote to IRS Commissioner David Kautter, urging him to drop what Grewal termed a “misguided” plan and cautioning it not to “play politics” or he would have to sue. Grewal pointed out that current federal tax law allows deduction of charitable contributions to state and local governments and that the New Jersey law is similar to 100 laws enacted in more than 30 other states and “consistent with longstanding IRS guidance and numerous court decisions that such contributions remain deductible.”

It does not appear that the IRS has not responded one way or another.

On July 17, Grewal joined with the states of New York, Connecticut and Maryland in suing the Treasury Department and the IRS over the SALT cap. The lawsuit, State of New York v. Mnuchin, 18-cv-6427, filed in federal court in Manhattan, seeks to block enforcement of the law and invalidate it as unconstitutional on the grounds that it amounts to double taxation that runs counter to the principles of federalism and was politically motivated.

While all of this has transpired, far less attention has been focused on the long-term implications of the tax law and how they are likely to impact programs such as Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid as well as funding for the arts, education, and just about anything other than military spending, which seems to be sacrosanct.

Those implications were the subject of a public talk given on June 26 in Asbury, New Jersey and repeated on October 6, in Clinton, New Jersey, by Columbia University economist Brendan O’Flaherty, former Director of Columbia’s Graduate Program in Public Policy and Administration and former Vice Chair of the Economics Department. O’Flaherty is the author of several books, most notably The Economics of Race in the U.S. (2015) and Making Room: The Economics of Homelessness (1998), both published by Harvard University Press. (He is also my husband.) A Power Point presentation that accomapnied the Ocotber 6 talk can be accessed here in pdf format.

Largely because of the massive tax cuts given to corporations under the tax bill, O’Flaherty predicts that the fiscal gap – a measure of how far short economic practices are from sustainability—which has already increased from 2.75% to 4% (nearly 50%) of the GDP (or $800 billion per year), will continue to grow, reaching 5.18% by 2025.

As O’Flaherty notes, that projection is based on the sort of best-case scenario in which the U.S. does not have to incur huge costs for such catastrophes as a major war, recession, epidemic or extreme damage caused by accelerating climate change.

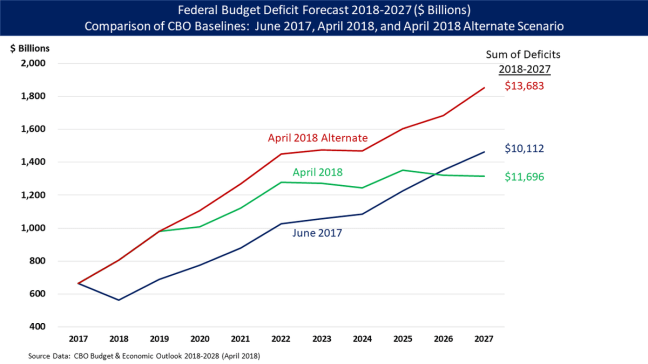

Looking at it using more common deficit terminology, the deficit is projected to exceed $1 trillion for the first time, by 2020. That is the conclusion of an analysis released by the Congressional Budget Office on April 9 of this year.

The CBO projects a steadily rising trajectory of federal debt over the next decade, with debt held by the public approaching 100% of GDP by 2028. The CBO attributes the marked increase in projected deficits to tax and spending legislation since mid-2017, especially the Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, along with the 2018 Budget and Consolidated Appropriations Acts.

A July 25, 2018 New York Times article analyzing the impact of the 2017 tax law said the amount of corporate tax collected by the federal government “has plunged to historically low levels in the first six months of the year, pushing up the federal budget deficit much faster than economists had predicted.”

Regardless of whether we look at the shortfall via the lens of deficit or fiscal gap, its immensity will force huge tax increases, massive spending cuts or both.

Those consequences will be felt by people in every state, not just New Jersey.

As harmful and unfair as the SALT deduction cap is, that problem pales in comparison.